Religion[1]

Instead of saying that only one religion is the true one, the Vietnamese are more apt to take the position that although one is right, others are not necessarily wrong. For instance, a man who makes offerings in a Buddhist temple probably pays reverence also at the ancestral altar in his own home in keeping with the teachings of Confucius you may even find Christ, Confucius, Mohammed and Buddha all honoured in the same temple.

Consequently, it is not too meaningful to say a certain percentage of the Vietnamese are Buddhists and another per cent something else. The percentages may be made up of individuals who are both Buddhists and something else.

The national constitution reflects the people’s belief in religious tolerance. It provides for freedom of religion, and states that no single religion is designated as the country’s official one.

Nevertheless, religion has been a significant factor in the Vietnamese way of life throughout history. The present culture and customs of these proud and sensitive people are strongly conditioned by their religious beliefs. For example, feeling that the universe and man’s place in it are essentially preordained and unchanging, they place high value on stoicism, patience, courage, and resilience in the face of adversity.

To get along in Vietnam you must have some understanding of these traditional beliefs. If for instance, you did not know that the parts of the human body are believed to possess varying degrees of worthiness – starting with the head – you would not see why patting a child on the head might be considered a gross insult. Or why it would be insulting for you to sit with your legs crossed and pointed toward some individual. Either of these actions would cause you to be regarded in a poor light by Vietnmese who follow the traditional ways.

Confucianism

Confucianism, a philosophy bought to Vietnam centuries ago by the Chinese, not only has been a major religion for centuries, but also has contributed immensely to the development of the cultural, moral and political life of the country. It established a code of relations between people. For example the relationship between sovereign and subject, father and son, wife and husband, younger and older people, friend and friend are governed by its teachings. Believing that disorders in a group spring from improper conduct on the part of the individual members, achievement of harmony is the first duty of every Confucianist

When he dies, the Confucianist is revered as an ancestor who is joined forever to nature. His descendants honour and preserve his memory in solemn ancestral rites. At the family shrine containing the ancestral tablets, the head of each family respectfully reports to the ancestors all important family events and seeks their advice.

Buddhism[2]

Confucianism exists side by side in many Vietnamese homes with Buddhism, a religion first taught in India some 26centuries ago. In Buddhism, the individual identity finds a larger meaning of life by establishing identity with eternity – past, present, future – through cycles of reincarnation. In the hope of eventual “nirvana,” that is oneness with the universe; he finds consolation in times of bereavement special joy in times of weddings and births.

Taoism

Like Confucianism and Buddhism, Taoism came to Vietnam from China centuries ago. Like Buddhism, its philosophy focuses the idea of man’s oneness with the universe.

Roman Catholics

About ten percent of the population of South Vietnam are of the Roman Catholic Religion, with some of these being the old Catholic ruling class of the North of Vietnam who fled to the south upon the defeat of the French by the Vietminh.

[1] Department of Defence

[2] This is expanded upon in the chapter “The Buddhist Monk”

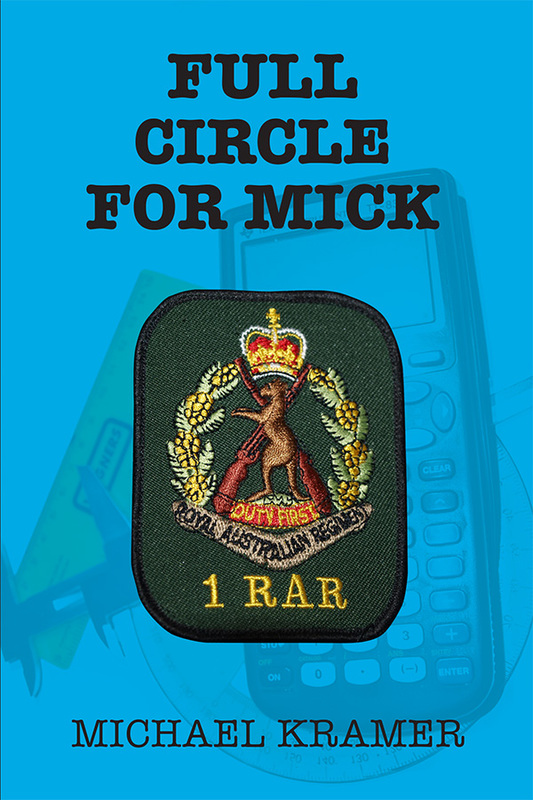

Title: Full Circle for Mick

Author: Michael Kramer

Genre: Historical Fiction

In 2013, Carolyn and Michael Georg Kaspar Friedrich Lampman applied for passports at the Albury Post Office and while hers went through immediately, (she is Australian born), his application resulted in a phone call being made to Department of Immigration and Citizenship (DIAC) and that department refusing him a passport on the grounds that his Australian Naturalisation Certificate “Did not say if his gender was male or female.” It did however; state that “Michael Georg Kaspar Friedrich Lampman presented himself before me at the Millicent Council Chambers on …. To swear allegiance to Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth the Second, her Heirs and Successors. This makes one wonder if the clerks at DIAC are conversant enough in the English language to know that “Himself” can only mean a male.

Michael’s reason for wanting his passport was to return to Vietnam and to fulfil his promise to a Buddhist Monk to return as a qualified engineer to help to rebuild the country that he had helped to destroy as a young Australian soldier in the Vietnam War during 1968 and 1969.

At a later date, DIAC cancelled his citizenship and papers, (he was a naturalised Australian Citizen, originating from Germany) even threatening to send him to jail for two years, for “Falsifying an Official Document,” resulting in him then using “Engineering Problem Solving Techniques” to rectify the situation as he was now also driving illegally on the grounds that in NSW it is not legal for someone to hold a driver’s licence unless that person has either “Approved Residency Status” or Australian Citizenship.

This is the story of a man’s battle and final victory against rampant bureaucracy, racism and PTSD. It deals with the first symptoms of PTSD, its diagnosis and its treatment and self-help strategies.

Author Bio

In 1967, he volunteered for service with the Australian Army in the Vietnam War, and was told that seeing how he was only twenty years old, he would need the signatures of his parents in order to join the army. Yet, the Australian Government was calling up males aged twenty years for service in the war if they wanted to serve or not. This prompted him to simply alter the date of birth on his Australian Naturalisation Certificate from 01/03/1947 to 01/03/1946 and he was in the army and this action was something that would become a problem forty five years later.

He went on to serve in Vietnam with the First Battalion of Royal Australian Regiment (1RAR) and continued to serve until he received a medical discharge some ten years later. As a treatment strategy for diagnosed PTSD, he was instructed to undertake tertiary studies which resulted in his better management of PTSD and his becoming a much better person as a result. In time, he was to undertake studies and now holds the Advanced Diploma of Mechanical Engineering, and the Associate Degree of Civil Engineering. He operates his own architectural and engineering drafting service, providing a high level of competent drafting work.

In 2010, he applied for an Australian passport which was refused by Immigration on the grounds that his Naturalisation Certificate did not list his gender. At a later date, the Australian Department of Immigration cancelled his Australian Citizenship papers, which have since been re-issued to him as well as an Australian passport. At a function held at his home, it was suggested that he put the experiences into a novel and this is the result.

Links

Author Website: http://mickkramer.com/

Smashwords: https://www.smashwords.com/books/view/573456

Bookpal: https://my.bookpal.com.au/Bookstore/b/10840-Full-Circle-for-Mick

Amazon.com

Amazon.co.uk

RSS Feed

RSS Feed